On Tuesday, New York City will hold primary elections for mayor and other local offices. It will be the second time the city is using “ranked choice voting” to select the Democratic and Republican nominees for its top office. Under New York City’s ranked choice rules, rather than cast their votes for just their top candidates, voters can rank as many as five preferred candidates from first through fifth.

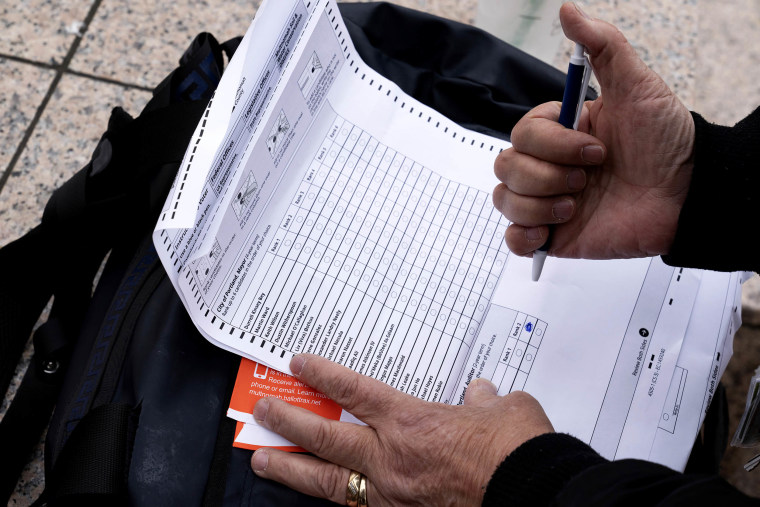

Enabling voters to rank candidates gives them an extra degree of input in a primary, but it also requires ranked choice ballots to be more complicated. In a typical non-ranked choice election, candidates have single buttons or bubbles next to their names on the ballot. In a ranked choice election, voters need the ability to select candidates as their first, second, third, etc. choices. On New York’s Democratic mayoral ballot this year, that translates into 60 bubbles, spread across 12 rows and five columns.

The grid style of ballot is more complex than a non-ranked one, adding new ways for voters to mismark or mistakenly fill out their ballots. While the rate of rejected ballots tends to be fairly small in ranked choice races, it happens about 10 times more often than in non-ranked races that appear on the same ballot, according to our recently published peer-reviewed research article in the journal Political Behavior.

Voters can mistakenly select the same candidate for multiple rankings (called “overranking”). They can select candidates for their first choices, leave the column blank for their second choices and select other candidates as their third choices (“skipping”). Or they can select multiple candidates as their first choices, for example (“overvoting”). Only overvoting is possible on a non-ranked ballot.

By analyzing over 3 million digital ballot records from over 150 ranked choice races in New York City, San Francisco, Alaska and Maine, the research shows that in a typical ranked choice race, about 4.8% of voters mismark their ballots in at least one way. The most common type of mismarks were overranks (selecting the same candidate multiple times) and skips (leaving a ranking blank but selecting a candidate for subsequent ranks).

New York City used ranked choice voting for its elections for mayor and other local offices in 2021, as well as for City Council races in 2021 and 2023. Averaging across those races, the analysis finds about 6.1% of New York City voters mismarked their ballots in at least one way. In the 2021 Democratic primary for mayor, the rate was 3.9%, while in the 2021 Republican mayoral primary, it was 6.9%.

How often are mismarked ballots rejected from being counted?

While mismarked ranked choice ballots are more common, they do not necessarily translate into uncounted votes. For example, in tabulating results, the New York City Board of Elections moves to the next valid ranking when it encounters a skip or an overrank.

Overvotes, however, can result in ballots’ being rejected — depending on where on the ballots they occur. Imagine a voter who overvotes the second ranking (by selecting two candidates as the second choice). If that voter’s first-choice candidate ultimately wins the election, the overvote in the second ranking would not result in the ballot’s being removed during tabulation.

But if the first-choice candidate is eliminated during the tabulation process, the invalid overvote for second choice would cause the ballot to be removed from the vote count.

Although about 5% of voters mismark their ballots in ranked choice races, only about 1 in 10 ballots with mismarks are “rejected” during vote tabulation.

Who mismarks their ballot?

Studying ballot image data tell us how a ballot was filled out — but not the identity of the voter who cast it. That poses a challenge for understanding whether certain types of voters are likelier than others to make mistakes on their ranked choice ballots.

In New York City, digital ballot records document the precinct from which each ballot came. That allows for comparisons among mismarking rates across 5,000-plus different precincts.

In the 2021 Democratic primary for mayor, mismarking rates in precincts where nearly all voters were Black, according to census data, were, on average, 3 percentage points higher than in precincts with almost no Black voters. Similarly, precincts with predominantly Hispanic voters had mismarking rates 4.4 percentage points higher than the rates in those with very few Hispanic voters.

Education and poverty also predicted mismarking rates on ranked choice ballots. Voters in precincts where nearly everybody has bachelor’s degrees mismarked their ballots at a rate 3.3 percentage points lower than voters in precincts where almost none have college degrees. Precincts with more people living below the poverty line had more mismarked ballots than more affluent precincts.

Leave a Reply